L’Io dell’Immagine

The Idea of one thing

RACCONTI D’ESTATE (6)

da “L ‘ Io dell’Immagine” Ambrosio Paolo

editore Albatros Il Filo SrL Roma 2019 ISBN 978-88-567-9768-8

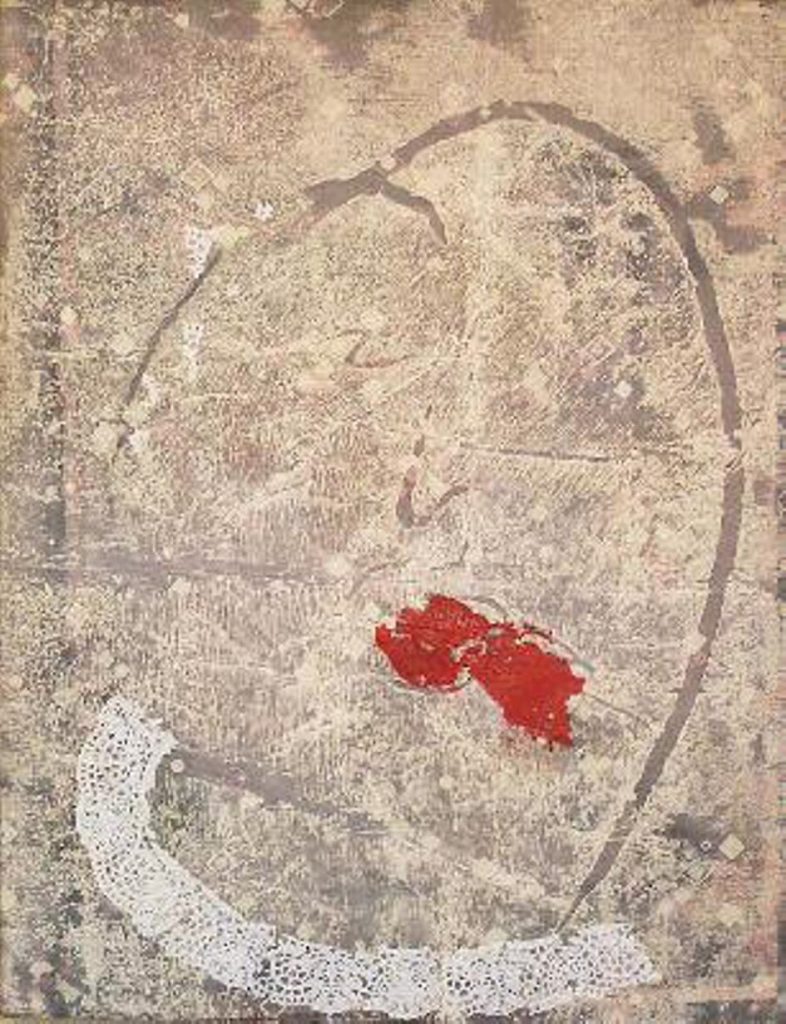

Sono un’immagine, nella gestazione, verosimilmente turbata. Non mi sento bella come la mia amica in bicicletta poichè sono nata in un momento di mia crisi ma egualmente utile per un viaggio nei labirinti silenziosi dell’anima. sono nata in un sogno e come sappiamo, i sogni non sono quasi mai precisi e ben distinguibili. Le mie fattezze incerte sollecitano la vostra interpretazione. La combinazione dei miei fattori corporei nel gioco delle linee e dei confini rivela dei momenti di pulsione del mio atteggiamento presente. Paolo Ambrosio me fecit, 2012, Senza titolo, tecnica mista su tela, cm.100×80.

I am an image, in gestation, probably disturbed. I don’t feel as beautiful as my friend on a bicycle as I was born in a moment of my crisis but equally useful for a journey into the silent labyrinths of the soul. I was born in a dream and as we know, dreams are almost never precise and clearly distinguishable. My uncertain features urge your interpretation. The combination of my bodily factors in the play of lines and boundaries reveals instinctive moments in my present attitude. Paolo Ambrosio me fecit, 2012, Untitled, mixed technique on canvas, cm.100×80

La Fondazione Ibsen ci ricorda che:

Gli organismi viventi che hanno mente, formano delle rappresentazioni neurali che possono diventare immagini confrontandosi con le tracce dell’organismo lasciate dall’ambiente. Il cervello dell’uomo possiede 100 trilioni di sinapsi 10 (14) e l’organizzazione della corteccia visiva è da qualche tempo, un soggetto di ricerca privilegiato. L’area della corteccia occipitale contiene una carta topografica dalla visione ove gruppi di neuroni presentano dei campi recettori che rispondono a diverse caratteristiche dell’oggetto percepito, come i contorni, gli angoli. Questi neuroni hanno delle connessioni chiamate proiezioni che sono inviate alle zone vicine alla corteccia visiva con caratteristiche specifiche come il colore e il movimento. Altre connessioni di questi neuroni sembra che abbiano una risposta di ricerca di riverbero. In un grado di analisi più fine le risposte alle informazioni di un neurone sono determinate dalla ripartizione delle sinapsi sulle ramificazioni. Numerose sinapsi sulle ramificazioni annesse alle terminazioni axonali sono situate su delle piccole escrescienze chiamate spine che si appoggiano sulle densità postsinaptiche dei dendridi recettori. L’analisi delle spine dell’ippocampo (struttura implicata nella memoria a breve termine) mostra un’organizzazione spaziale criptata che favorisce l’integrazione temporale delle informazioni richieste per la plasticità sinoptica. Forme ed estetismi sono determinati più dall’ambiente in cui appaiono nello spazio e nel tempo che da noi immagini di come ci presentiamo agli occhi.[12]

L’oggetto viene esaminato attraverso una successione di occhiate ognuna delle quali ricade ogni volta sullo stesso punto dell’occhio, cioè la fovea, la parte centrale della retina. Con occhiate successive si costruisce uno schema che contiene l’intera scena come in una riga di parole scritte al computer. Il processo del guardare è attivo e selettivo ed è guidato dai processi di filtrazione e altri processi che determinano ciò che conserviamo in una sequenza di fissazioni. Questi processi dipendono dall’attenzione dell’osservatore e dalle sue intenzioni percettive. Ruggero Pierantoni chiarisce come il nostro senso della vista ci aiuti nell’esplorazione visiva. L’occhio non è una camera oscura immobile ma spazza, per così dire, ininterrottamente l’immagine attraverso una serie di piccoli movimenti. Questi piccoli attimi di fissazione portano le porzioni dell’immagine alla zona della retina chiamata fovea. La fovea è popolata da un gran numero di unità di coni fotorecettori preposti alla visione del colore. Questa miniaturizzazione della visione mediante i coni (ciascuno un millesimo di millimetro) ci permette un’analisi fine dotata della migliore resa dei dettagli nel fenomeno percettivo. Quindi i continui movimenti dell’occhio servono a portar sulla fovea, in successione temporale, i dettagli più importanti della scena che stiamo osservando. Si tratta di un permanente andare e riandare dell’occhio su quel punto o su quell’altro le cui linee ideali, cioè le traiettorie seguite dall’occhio non sono per nulla rettilinee. In questo modo non viene mantenuta neppure la possibile relazione spazio-tempo. I movimenti esploratori sono, infatti, di tipo impulsivo o balistico e non continui, sono moti di spazzamento, esattamente come avviene nella scansione televisiva delle immagini. Durante l’esplorazione visiva, l’occhio spazza l’immagine con tre tecniche: un’oscillazione lenta, salti bruschi e veloci e piccole velocissime vibrazioni locali. L’occhio si muove durante la visione ma sorprendentemente le immagini rimangono ferme. I movimenti servono a portare sulla fovea le regioni a maggiore intensità d’informazione. Vi è quindi una grande attività del campo visivo, in cui si assiste a una comparsa e scomparsa di settori di campo visuale. Se invece l’immagine stabilizzata è dotata di significato la comparsa e scomparsa di parti dell’immagine avverrà per zone organizzate. Questo fenomeno mostra come certe immagini che abbiamo appreso come entità autonoma tendono a resistere all’erosione biochimica della visione stabilizzata e l’occhio finisce di riconoscerle a grandi tratti. [13]

The Ibsen Foundation reminds us that:

Living organisms that have minds, form neural representations that can become images by comparing themselves with the traces of the organism left by the environment. The human brain has 100 trillion synapses 10 (14) and the organization of the visual cortex has for some time been a privileged subject of research. The area of the occipital cortex contains a topographical map from the vision where groups of neurons have receptor fields that respond to different characteristics of the perceived object, such as the contours, the angles. These neurons have connections called projections that are sent to areas close to the visual cortex with specific characteristics such as color and movement. Other connections of these neurons appear to have a reverb search response. In a finer degree of analysis the responses to neuronal information are determined by the distribution of the synapses on the branches. Numerous synapses on the branches attached to the axonal terminations are located on small excresciences called spines which rest on the post-synaptic densities of the dendrid receptors. The analysis of the hippocampal spines (structure involved in short-term memory) shows an encrypted spatial organization that favors the temporal integration of the information required for synoptic plasticity. Shapes and aesthetics are determined more by the environment in which they appear in space and time than by us images of how we present ourselves to the eyes.(12)

The object is examined through a succession of glances, each of which falls each time on the same point of the eye, that is, the fovea, the central part of the retina. With successive glances, a scheme is built that contains the entire scene as in a line of words written on the computer. The process of looking is active and selective and is driven by filtration and other processes that determine what we store in a sequence of fixations. These processes depend on the observer’s attention and his perceptive intentions. Ruggero Pierantoni clarifies how our sense of sight helps us in visual exploration. The eye is not an immobile dark room but sweeps the image, so to speak, continuously through a series of small movements. These small moments of fixation bring the portions of the image to the area of the retina called the fovea. The fovea is populated by a large number of units of photoreceptor cones responsible for color vision. This miniaturization of vision by means of cones (each one thousandth of a millimeter) allows us a fine analysis with the best rendering of details in the perceptual phenomenon. Therefore, the continuous movements of the eye serve to bring the most important details of the scene we are observing to the fovea in temporal succession. It is a permanent going and going back of the eye on that point or another whose ideal lines, that is, the trajectories followed by the eye are by no means straight. In this way not even the possible space-time relationship is maintained. The exploratory movements are, in fact, impulsive or ballistic and not continuous, they are sweeping motions, exactly as occurs in the television scanning of images. During the visual exploration, the eye sweeps the image with three techniques: a slow oscillation, sudden and fast jumps and small very fast local vibrations. The eye moves during viewing but surprisingly the images remain still. The movements serve to bring the regions with the greatest information intensity to the fovea. There is therefore a great activity of the visual field, in which we witness an appearance and disappearance of sectors of the visual field. If, on the other hand, the stabilized image is endowed with meaning, the appearance and disappearance of parts of the image will take place in organized areas. This phenomenon shows how certain images that we have learned as an autonomous entity tend to resist the biochemical erosion of stabilized vision and the eye finishes recognizing them in large sections.(13)

La vocazione a creare consiste nella chiamata dell’immaginario, che riguarda l’indeterminato e a ciò che è in via di definizione. L’occasione, così come l’entusiasmo è accidentale e fortuita ma imprescindibile e necessaria. Non costituisce un vero pretesto, che sarebbe troppo poco, o una causa, in cui si tenderebbe invece a vedere troppo.

The vocation to create consists in the call of the imaginary, which concerns the indeterminate and what is being defined. The occasion, as well as the enthusiasm, is accidental and fortuitous but essential and necessary. It does not constitute a real pretext, which would be too little, or a cause, in which one would tend to see too much

I.: Come dice Kierkegaard con la logica si può mostrare la realtà compiuta dell’idea ma senza occasione questa realtà non potrebbe mai divenire reale. L’occasione tra tutte le categorie è certamente la più divertente e spiritosa, essa passeggia tra noi immagini come un elfo ed è qualcosa solo in rapporto a ciò che essa, appunto, occasiona. Essa è la vera e propria categoria di passaggio dalla sfera dell’idea alla realtà. Noi immagini viviamo anche un’altra estetica dell’occasione non fondata sul carattere inaspettato e istantaneo dell’esperienza ma che pensa l’arte come lavoro continuo piuttosto che come estro e novità assoluta. È l’occasione più come opportunità permanente che come circostanza istantanea. In questo caso non d’ispirazione bisogna parlare ma di composizione dell’indeterminato che genera incanto. L’irrazionale subentra nel cognitivo poiché le decisioni non sono semplicemente frutto di esso ma dipendono dell’emotività del momento. Ciò che importa nel processo artistico non è più il rapporto ispirazione-occasione ma quello di esercizio-occasione, poiché si connette a qualcosa di già intuito ma di non completamente pensato e realizzato.[14] Le opere d’arte sono segni iconografici privi di convenzioni di lettura capaci di sviluppare visibilità, sonorità, emozioni ed hanno una funzione estetica a differenza della conoscenza che ha solamente valore gnoseologico.

I .: As Kierkegaard says with logic you can show the completed reality of the idea but without the occasion this reality could never become real. The occasion of all the categories is certainly the most fun and witty, it walks among us images like an elf and is something only in relation to what it, in fact, causes. It is the real category of transition from the sphere of idea to reality. We images also experience another aesthetic of the occasion that is not based on the unexpected and instantaneous character of the experience but which thinks of art as a continuous work rather than as inspiration and absolute novelty. It is the occasion more as a permanent opportunity than as an instant circumstance. In this case we must not speak of inspiration, but of the composition of the indeterminate that generates enchantment. The irrational takes over the cognitive since decisions are not simply the result of it but depend on the emotionality of the moment. What matters in the artistic process is no longer the inspiration-occasion relationship but that of exercise-opportunity, since it connects to something already intuited but not completely thought and realized.(14) The works of art are iconographic signs devoid of reading conventions capable of developing visibility, sounds, emotions and have an aesthetic function unlike knowledge which has only gnoseological value.

I.: A tal riguardo chi guarda dentro di noi, nella nostra coscienza, è Merleau-Ponty nella sua “Esthètique”: «In fin dei conti le pitture sono anche delle finestre che ci fanno assistere, come da feritoie direttamente nella scorza delle cose, nella genesi sorda dell’essere, al brulicante spettacolo in un istante; e anche gli occhi sono degli specchi che raccolgono le specie ontologiche, si riempiono dell’essere stesso saturato di metamorfosi per uscire dal sé e rientrare in sé». Nell’immagine non c’è l’inganno della coscienza umana, ma c’è la nostra coscienza poiché ciò che conduce a riconoscere l’arte come altro da sé della realtà esistenziale è un libero processo. Coscienza non empirica ma pura che pone l’arte come realtà diversa e nuova eliminando tendenzialmente ogni possibilità d’illusione e d’inganno. La nostra influenza, in quanto immagini, sullo spettatore connessa alle molte strutture cerebrali dell’uomo che sono coinvolte nella regolazione delle emozioni; tra queste funzioni vitali abbiamo certamente il piacere, che risiede nelle forme biologiche dell’ipotalamo e del lobo limbico. Gli esperimenti di Olds e Milner 1954 hanno riconosciuto l’ipotalamo laterale il centro del piacere.[15] Il piacere deriva dal desiderio, dall’eccitazione nel vedere immagini nuove, che attiva appunto i cosiddetti centri del piacere dell’ipotalamo laterale e del lobo limbico, sino ad entrare in un vero e proprio orgasmo attraverso l’attivazione dell’ossitocina.

I .: In this regard, the one who looks inside us, in our conscience, is Merleau-Ponty in his “Esthètique”: “After all, the paintings are also windows that let us see, as if through slits directly in the bark of things , in the deaf genesis of being, to the teeming spectacle in an instant; and even the eyes are mirrors that collect ontological species, they are filled with the very being saturated with metamorphosis in order to come out of the self and re-enter itself “. In the image there is no deception of the human conscience, but there is our conscience since what leads to recognizing art as other than itself of existential reality is a free process. Not empirical but pure awareness that places art as a different and new reality, basically eliminating any possibility of illusion and deception. Our influence, as images, on the viewer is connected to the many human brain structures that are involved in the regulation of emotions; among these vital functions we certainly have pleasure, which resides in the biological forms of the hypothalamus and the limbic lobe. Olds and Milner’s 1954 experiments recognized the lateral hypothalamus as the center of pleasure.(15) The pleasure comes from desire, from the excitement of seeing new images, which activates the so-called pleasure centers of the lateral hypothalamus and the limbic lobe, up to entering a real orgasm through the activation of oxytocin.

L’opera d’arte è qualcosa che, per la sua complessità di lettura, spesso non traspare completamente ma rimane nascosta nel suo significato più profondo. Questa difficoltà di percepire produce una scarica di stimoli e di segnali che generano a livello visivo un’impressione straordinaria, dal momento che l’uomo è essenzialmente un animale visivo. La curiosità e il desiderio irresistibile di scoprire, sollecitati dal mistero dell’arte spingono l’uomo attraverso un’azione pro-serotoninica a cercare incessantemente il piacere.[16] Nel sedersi, al teatro delle emozioni davanti all’Io, il desiderio non diviene un fine ma una parte in gioco che, presa nelle apparenze superficiali, si muove in un mondo i cui protagonisti non si conoscono.

Nasce un’idolatria dell’immagine, una forma di religione, quella dell’arte, con le sue opere reliquia, i suoi templi di artisti e le sue processioni di visitatori che sostano davanti a ogni immagine che certifichi il loro credo. È utile, nell’avidità dello sguardo, cancellare la naturalità dell’oggetto e trasformarlo in uno specchio che rifletta il desiderio, scegliendo la ricerca del piacere attraverso la linea d’azione più consona al proprio desiderio.

The work of art is something that, due to its complexity of reading, often does not fully shine through but remains hidden in its deepest meaning. This difficulty in perceiving produces a discharge of stimuli and signals that generate an extraordinary impression on a visual level, since man is essentially a visual animal. Curiosity and the irresistible desire to discover, stimulated by the mystery of art, push man through a pro-serotonin action to relentlessly seek pleasure.(16) In sitting down in the theater of emotions in front of the ego, desire does not become an end but a part in play that, taken in superficial appearances, moves in a world whose protagonists do not know each other.

An idolatry of the image is born, a form of religion, that of art, with its relic works, its temples of artists and its processions of visitors who stop in front of every image that certifies their belief. It is useful, in the greed of the gaze, to erase the naturalness of the object and transform it into a mirror that reflects desire, choosing the pursuit of pleasure through the line of action most suited to one’s desire

La ferita dell’esistenza è stata falsamente guarita da uno spettacolo che rende invisibile la realtà e alterata la vita. Nell’arte resiste la speranza di una metamorfosi che proceda per trasformazioni successive, capaci di generare un cambiamento qualitativo del sistema sociale, che renda ciò che appare inevitabile impossibile.

The wound of existence has been falsely healed by a show that makes reality invisible and life altered. In art there is the hope of a metamorphosis that proceeds by successive transformations, capable of generating a qualitative change in the social system, which makes what appears inevitable impossible.

[12] Altman Jennifer, Micro, meso, et macro connectomiques cérébrales, Fondation Ibsen, Alzheimer Actualités n. 235

[13] Pierantoni Ruggero, L’occhio e l’idea, fisiologia e storia della visione, Boringhieri, Torino, 1982, pp. 185, 186, 187

[14]Perniola Mario, Due estetiche dell’occasione, Rivista di Estetica Università di Torino n. 13, 1983, p.11

[15] Maffei Lamberto, Fiorentini Adriana, Arte e cervello, cit., pp.61, 62

[16] Maffei L., Fiorentini A., Arte e cervello, cit., pp. 62-63